How to Read The Wind.

Sailing is easy. It is learning to read the wind that is challenging. You can not see the wind. You can only see results of the wind. You must train your eye to look for wind indicators. Some wind indicators to look for while on or near the water are: flags, smoke, anchored boats, throw sand in the air, long hair and ripples on the water.

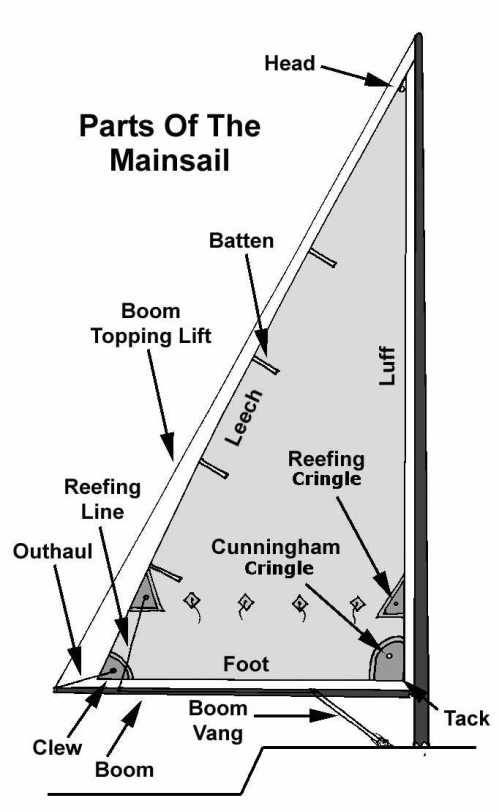

You can also use your boat to find the wind if necessary. Let the main sail (rear sail) out completely, turn the boat until the boom (horizontal support at bottom of sail) comes in over the center of the boat, the front of the boat is now pointed at the wind direction. Ripples on the water are one of the best natural wind indicators because they are around you all the time and they also help estimate the wind speed. The bigger the ripple, the stronger the wind.

Wind is one of the trickiest elements for the new sailor to become attuned to because it can only be observed indirectly. We have moving air around us all of our lives, but people are oblivious to it. Because sailing a vessel uses wind, a sailor who is aware of where the wind is and its shifts is advantageous.

The ocean is the largest surface on the earth and with disruptions caused by various land features, along with the differences in the rate that air masses heat and cool, the result is incessantly moving air—wind. Land areas warm and cool more rapidly than bodies of water. For that reason, cooler, denser air often flows from the water toward land, a sea breeze, during the day, and from the land toward water at night. Because the temperature contrast is usually greater during the day in summer, the sea breeze is usually stronger.

Before leaving the dock, take notice of wind conditions by being aware of speed and direction. Most harbors have some kind of flag, burgee or banner that functions not only as a nautical emblem, but it can also indicate what is going on with the wind. Flapping wildly means—you guessed it—lots of wind; hanging straight down, a lack of wind; and alternating in between the two likely means puffy conditions. At the top of many sailboat masts is a wind fly, which will point in the direction the wind is coming from. Pieces of yarn tied to the stays, also let the sailor know the wind direction. The wind can also be sensed with the ears, face, or hands.

Look at anchored boats to help indicate wind direction, but remember that current can complicate the picture. If there is no current, a boat will point into the wind. If the current is stronger than the wind, however, they may point in the direction of the current. If the wind and current are exerting about the same force on a boat, it will point midway between the current and wind directions.

Wind lines formed by puffs of stronger wind will make the water appear darker and choppier as it advances toward the boat. Whitecaps form when the wind is between 11 to 16 knots. Below this speed, it takes some practice to see wind lines. And in light air one might be sailing with mere ripples visible on the water. Once sailing, a good exercise is to watch for changes in wind speed and call the puffs and lulls out. Also bear in mind that currents can also distort the appearance of the wind on the water. Anytime the current flows against the wind, choppier waters result. When the current flows with the wind, the water appears calmer.

The important thing about wind is that the speed and direction are always shifting and require continual monitoring. Sometimes the boat experiences favorable wind shifts called lifts that allow a boat to point higher into the wind. Other times the boat experiences headers, which force the boat to sail lower than the desired course.

How the air interacts with headlands, swirls off city buildings, or funnels through bridges affects how boats sail. Other boats nearby can likewise produce a change in wind speed. Race boats use their sails to blanket the wind from each other to assert tactical advantages. Large ships can also block wind and create large windholes. Terrain can amplify wind speed since a narrow strait of water between two promontories is likely to funnel and accelerate wind. Long expanses of unobstructed water also have an effect on sea state, allowing wind to sweep across the surface and build wavelets into chop, and chop into swells.

It is also good to recognize that the wind you feel at sea level is related to the clouds above you. Do the bottom layers of clouds move faster than the top layers? Are the clouds and the wind you feel moving in the same direction? Is there a clearing trend or are the clouds billowing up into intimidating thunderheads? Is the wind you experience sucking you toward them? Noting conditions before you leave the dock will give you something of a benchmark once you get underway.

One can read information about the wind from other sailboats as well. A boat upwind several miles away heeling over on its ear while you are barely moving means more wind is heading your way. Conversely, a boat upwind that seems to be flat and listless means a lull lies in that direction. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that a sailboat returning with its crew in full foul-weather gear and with a reef in the main has seen some breeze, and that if you are just heading out, you might do well to put a reef in as well.

And it doesn’t take a genius to figure out the best way to learn about wind is to get out and sail in it. So stop reading, and start sailing!

Check out the NOAA website for further weather related information.

Check out the Beaufort Wind Scale here.

A deep sail provides more power for punching through waves while a flatter sail creates less drag. A flatter sail also creates less drag, is faster in smooth water, and also creates a wider angle of attack for pointer closer. A flatter shape is better in heavy air when a boat is overpowered.

A deep sail provides more power for punching through waves while a flatter sail creates less drag. A flatter sail also creates less drag, is faster in smooth water, and also creates a wider angle of attack for pointer closer. A flatter shape is better in heavy air when a boat is overpowered.